A founder writes a thesis (condensed)

Getty Images. Soprano Angel Blue stars as Magda in The Metropolitan Opera’s 2024 production of Puccini’s La Rondine.

As some may know this last May I graduated with a Performing Arts Administration degree from NYU and the last thing to solidify my diploma and my thousands of dollars in student loan debt I had to write a final paper. At first I wanted to write about salons, their history, and how they can act as a means of introducing Millenials and Gen Z to classical music today as a third space; however, digging into more I discovered the topic was too narrow and lacked the amount of literature needed to be able to write a full blown paper for the degree’s sake. From that I moved to an even more important topic that is not talked about enough in the opera industry and is an important part of Salon Avec Moi —audience and artist diversity and engagement.

For most of us it only makes sense that people want to see themselves represented in the world around them whether that means in art, media, industries, community, and more, and yet the opera world has yet to really make that connection. This conversation has just been rekindled, if not only begun, for the first time to leadership since the COVID-19 pandemic with the Black Lives Matter movement for many industries especially opera. Since, many academics, administrators, and artists have released literature on representation both onstage and off to shine more light and solidify its importance and their experiences for people of color and the LGBTQ+ community. Furthermore, of note, literature for LGBTQ+ individuals in classical spaces like opera is practically nonexistent (as a lesbian the one huge moment of literature found in En Travesti by Corrine Blackmer and Patricia Juliana Smith made me sob from feeling seen while reading only the first chapter).

Literature from the paper and others I discovered during research.

For this paper I focused on the history of people of color in opera and honing in in particular on The Metropolitan Opera’s history, filling the gaps in my own knowledge of how opera got here and how deeply embedded its racism is within not only the artistry but the industry itself. This version I share with you is a condescend version meant for journal publication albeit still long, but includes research from those I’ve shared spaces with, interviews who lended me their time, insights, and experiences, to which the paper would not have been the same without them.

**Trigger Warning**

This contains historical images of misappropriation and racism including blackface and yellowface.

The Metropolitan Opera Standard: Understanding Systemic Racism in Opera and its Impact on Young Arts Audiences in the United States

Abstract

The opera industry in the United States holds a history of racism embedded in its artistry, programming, staffing, casting and more that has lasted for centuries from its Westernized culture and American upbringings that art administrators and audiences still face today while the industry tries to usher in new diverse, young audiences and increase BIPOC inclusivity and visibility both onstage and off as America nears closer to the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections finding America will shift from a White majority society to a BIPOC majority society by 2045. While other performing arts industries make headway in diversity, equity, and inclusion, opera has a unique challenge from its systemic history that has seemingly been engraved in its art and has taken longer to shed itself from. This study aims to explore how the history of systemic and cultural racism within the American opera industry, art form, and Level A opera institution The Metropolitan Opera, impacts the diversity in casting and storytelling onstage today and influences current young arts audiences age 54 and under attendance, barriers, and perceptions in the United States.

Keywords

Opera; BIPOC; Diversity; Young Arts Audiences; Systemic Racism

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. Introduction

The opera industry in the United States holds a history of racism embedded in its artistry, programming, staffing, casting and more that has lasted for centuries from its Westernized culture and American upbringings that art administrators and audiences still face today while the industry tries to usher in new diverse, young audiences and increase BIPOC (Black and People of Color) inclusivity and visibility both onstage and off as America nears closer to the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections finding America will shift from a White majority society to a BIPOC majority society by 2045 (Cherbo and Peters 1992, Cuyler 2021; Stein 2020). While other performing arts industries make headway in diversity, equity, and inclusion opera has a unique challenge from its systemic history that has been engraved in its art and has taken longer to shed itself from.

Spanning decades of time, ties to racism, exoticism, minstrelsy, orientalism, and the art form’s pushback on opera’s auditory-first experience in the industry has kept BIPOC artists, conductors, and composers hidden from America’s opera industry and left out of the art form while stories of White and European groups, history, and nationality were being told at the industry’s highest classical standard in America and one of the most well-known houses that even those who have never been to the opera are well aware of—the Metropolitan Opera (André 2018; Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016; Yoshihara 2007). Upon the opera’s surgency in the United States with now the largest classical arts institution in America, the Metropolitan Opera (the Met Opera), the institution experienced a level of innate segregation early on that has impacted the institution still to this day. Black and people of color’s arrival upon existence in these prestigious, “high-brow,” and high-level spaces came decades after the onset of the institution and would be presented and casted in specific, and in most times, reductive ways that would relate to stereotypes to their race and culture and if not left out of the traditional canon, once more displayed in negative characterizations that can be tied to their race.

History of BIPOC representation in opera involves deep rooted racism put on display in multitudes of traditional operatic canon including but not limited to blackface, yellowface, harmful racial tropes and stereotypes, as well as misappropriation onstage with works that exoticize people of color through works like Aida and Madama Butterfly,affecting limitations and preconceptions to BIPOC casting, abilities, opportunities, and even connotations to their race and being a classical artist (André 2018; André, Bryan, Saylor 2012; Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016).

With the current opera audiences in America at prestigious and opera leader institutions like the Met Opera containing a majority of White audiences and only in the last year as of June 2024 decreasing their average single-ticket buyer age to 44 from 50 before the COVID-19 Pandemic, on top of the U.S. Census Bureau’s findings on upcoming United States demographics in 2045, it is imperative for the opera industry and its institutions like the Met Opera to usher in young and diverse arts audiences to the opera or face the consequences of an even more pressing time of financial turbulence that the institution has already been facing post pandemic with a $3.5 million dollar settlement to ex conductor James Levine and several dips into the Met Opera’s endowment fund—a staggering total of $73 million.[1]

This aims to explore how the history of systemic and cultural racism within the American opera industry, art form, and Level A opera institution, the Metropolitan Opera, impacts the diversity in casting and storytelling onstage today and influences current young arts audiences age 54 and below attendance, barriers, and perceptions in the United States.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Javier C. Hernández, “Audiences Are Returning to the Met Opera, but Not for Everything: The Met Is Approaching Prepandemic Levels of Attendance. But Its Strategy of Staging More Modern Operas to Lure New Audiences Is Having Mixed Success.,” The New York Times, June 13, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/arts/music/met-opera-attendance.html.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2. Literature Review

2.1 History of BIPOC Representation and Artistry in Opera

2.1.1 Black Artist Access Points and Representation

Opera in America since its inception has held a complicated history beginning as an organization in 1883 and with the Met Opera’s home itself at the Lincoln Center—although a center for art in the city for decades to come—onset the displacement of more than 7,000 lower-class families and 800 businesses in an area that was predominantly Black and Hispanic, deepening segregation upon its groundbreaking in 1959.[2] Through its history literature has discussed and documented BIPOC firsts at the institution, predominantly with Black and Asian artists, as the inclusion of other marginalized groups have been sparce since its inception that we still see today. Of note, BIPOC artists have made appearances in opera houses and were present in opera spaces well before their appearances at the Met Opera, and faced oppression from White leadership in many spaces in gaining access because of leadership’s racist ideologies in relation to opera singing and their “capability” due to harmful and dangerous stereotypes on education, anatomy, negative thoughts on displays of biracial romance in opera love stories[3], or catering the experience to their White audiences and their experiences (Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016). This additionally positions André’s pressing question on Black and people of color in opera, especially when we look to the traditional opera canon—who gets to sing, who is telling the story, and who interprets the story (André 2018).

Of the most prominent firsts for Black artists at the Met Opera were African Americans Marion Anderson and Leontyne Price. Notably both women, Anderson would see herself as the first Black opera singer at the Met Opera in her Met debut in the leading role of Ulrica in Un ballo in maschera in 1955—72 years after the Met Opera organization began. Previously only performing in many concert halls with art song repertoire, this role for Anderson was small—only entering for one scene in the entirety of the opera, set to her character in this production as the “negro fortune teller,” setting herself apart through the character’s ethnic characterization and class status along the role of “Creole.” Although Ulrica and Anderson’s presentation in the opera did not involve negative connotations to minstrelsy and Black people, it does affirm the use of exoticism and “otherness” of BIPOC artists when cast in traditional operatic canon.

Following the debut of Anderson, soprano Leontyne Price would make her Met debut three years before the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964 in the role of Leonora in Verdi's Il Trovatore well into her international operatic career. Price successfully permeated the traditional operatic canon in prestigious opera houses in the world including the title role in Verdi’s Aida at the Met Opera. The role of Leonora does not have negative underlying meanings to ethnicity; however, it is important to note the title role of Aida is a Black character with a love story tied to falling in love with a White man and dying in the end because of it—a role associated to her relationship to Whiteness.

The roles both Anderson and Price played specifically with Un ballo in maschera and Aida present both operas are written from the perspective of White, European men who lack an understanding of what it is like to live a Black or person of color experience, and yet, write roles and operas based on those very experiences, destined to fall into tropes and stereotypes if not given careful attention in an operatic canon that already excludes stories of BIPOC experiences, creating more limitations to how Black and people of color can exist within the space, all while casting White singers moreover than BIPOC artists in those roles.

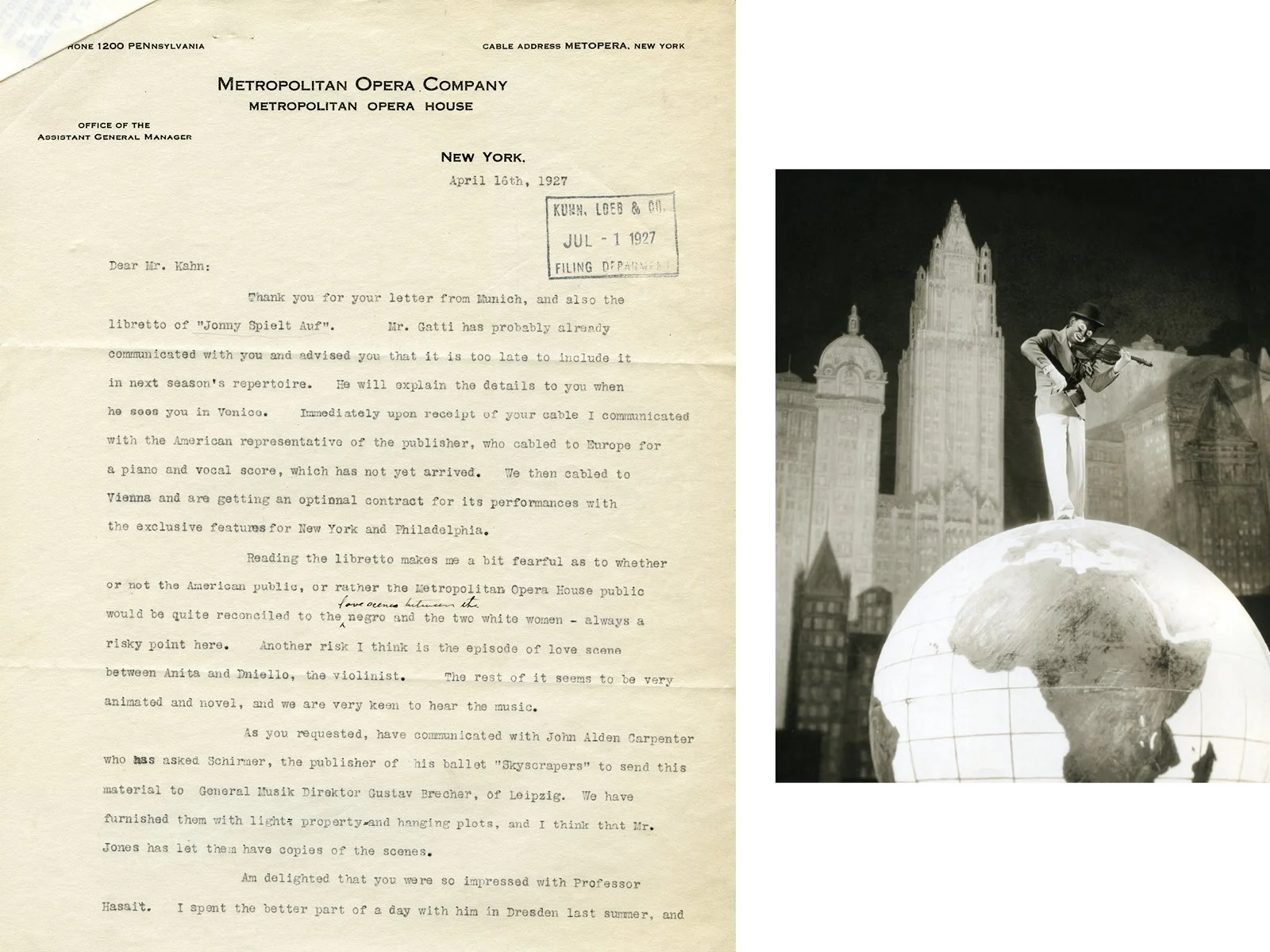

Met assistant manager Edward Ziegler identified interracial romance as a potential “risky point” with the Metropolitan’s public in 1927. (Otto H. Kahn Papers, Princeton University Library)

German baritone Michael Bohnen (wearing blackface makeup) in the title role of Jonny Spielt Auf at the Met in 1929 (Met Archives)

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[2] Whyte, William Hollingsworth. The Exploding Metropolis. University of California Press eBooks, 1993. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA21688871.

[3] Documentation of a letter where Met Opera assistant manager Edward Ziegler identified interracial romance as a potential “risky point” with the Metropolitan’s public in 1927. “Part 1 Section 1,” Metropolitan Opera, n.d., https://www.metopera.org/discover/archives/black-voices-at-the-met/part-1-section-1/#:~:text=The%20Met%27s%20limited%20inclusion%20of,Enlarge%20Image.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2.1.2 Asian Artist Access Points and Representation

The auditory-first argument for the opera art form finds itself more embedded in the casting and characterization of Asian roles as well as the double standard of Western orientalism placed on Asian opera artists, impacting the opportunities in which those groups gain access to the Western, globalized opera world albeit classical music world,leaving limited literature and exploration to dive into the careers of Asian opera singers who have made it to the Met Opera. However, we look to two Asian women who successfully achieved different levels at the top—Hei-Kyung Hong and Tamaki Miura.

Korean opera soprano Hei-Kyung Hong made her Met debut as Servilia in Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito in 1984 as the first Asian opera singer to debut a leading role at the Met Opera, opening the door for more Asian opera singers, going on to an international career, and to sing more than 370 Met Opera performances in other roles like Mimì in Puccini’s La bohème, Adina in Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore, Susanna in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, Liù in Puccini’s Turandot, and Violetta in Verdi’s La traviata.[4] Of note the majority of these roles do not have ethnic correlations to their casting and are cast moreover by White artists including the role of Liù in Puccini’s Turandot—a role that is described as a “slave girl” that should as the opera’s setting takes place in Peking be played by an Asian artist (as most of the roles in the show) but routinely is cast with White artists.

Tamaki Miura’s journey, although only performing an excerpt from Madama Butterfly at a war benefit concert at the Met Opera and not a leading role in a production, presents the question once more of who gets to sing, who is telling the story, and who interprets the story.[5] Miura made a career in performing Madama Butterfly’s Cio-Cio-San, European Puccini’s composition telling a story of Japanese geisha Cio-Cio-San (Madama Butterfly) and the misfortune that falls upon her from a visit of an American, White soldier during wartime, post war after giving birth to his child out of wedlock turns to killing herself upon his return to Nagasaki with his American wife. Even with Butterfly’s distorted representation of Japanese culture that takes place in the opera, notably the leading role of Cio-Cio-San being a geisha, fuels orientalism of Japanese womanhood for White audiences. These audiences would describe Muira’s performance as “natural” and “innate”—descriptions solely based on her ethnicity and race rather than talent and success in such a role—as well as projections from the character of Cio-Cio-San’s Western orientalist feminine fantasies put on the role as descriptors for review of Miura herself and her performance; however, noticeably when White artists sing (and often do) roles that belong to Asian characters like Cio-Cio-San and Suzuki in Madama Butterfly or Turandot and Liù in Turandot, they are met with fantastical praise in no association with character traits of the role itself but as themselves as individuals, implicating Asian performers in Asian roles satisfy a sense of realism for White and European opera audiences that innately has orientalism and racism embedded in its perceptions (Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016).

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[4] “A Rare Revival of Gluck’s Orfeo Ed Euridice Opens at the Met on October 20,” Metropolitan Opera, n.d., https://www.metopera.org/about/press-releases/a-rare-revival-of-glucks-orfeo-ed-euridice-opens-at-the-met-on-october-20/#:~:text=Korean%20soprano%20Hei%2DKyung%20Hong,Violetta%20in%20Verdi%27s%20La%20Traviata.

[5] André, Naomi. Black Opera. University of Illinois Press eBooks, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5622/illinois/9780252041921.001.0001.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2.2 Misappropriation of BIPOC Identities in the Exclusion Era

2.2.1 Minstrelsy and Blackface

The history of the popularization of minstrelsy in America and how it impacted BIPOC characters not only in the American opera industry but across the world proves to add levels of complexities to the opera industry’s auditory-first argument in casting for the roles in which people are trained for, regardless of race, gender, and the like, as well as audience perceptions and acceptance of Black characters and singers in opera, and the development of an operatic tradition in the United States (André, Bryan, Saylor 2012; Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016).

Minstrelsy’s history in America provided an opportunity for White performers to dominate and mimic African Americans, creating uninhibited and transgressive spaces to embody “the other” as well as a space for White audiences to imagine a time with tropes of “benevolent slaveholders,” peaceful plantation,” and “happy workers.” These spaces, although harmful and challenging were also an opportunity for African Americans to perform. While performance opportunities rose, minstrel companies, touring concert companies, and Black opera companies would intertwine, performing on the same stages as touring opera companies, resulting in the blending of opera and minstrel audiences together along the way well into the 20th century as well as the depiction of Blackness in musico-dramatic settings in both storylines, characterization, and visual presentation in harmful tropes and the use of darkening makeup on light tone skin otherwise known as Blackface.

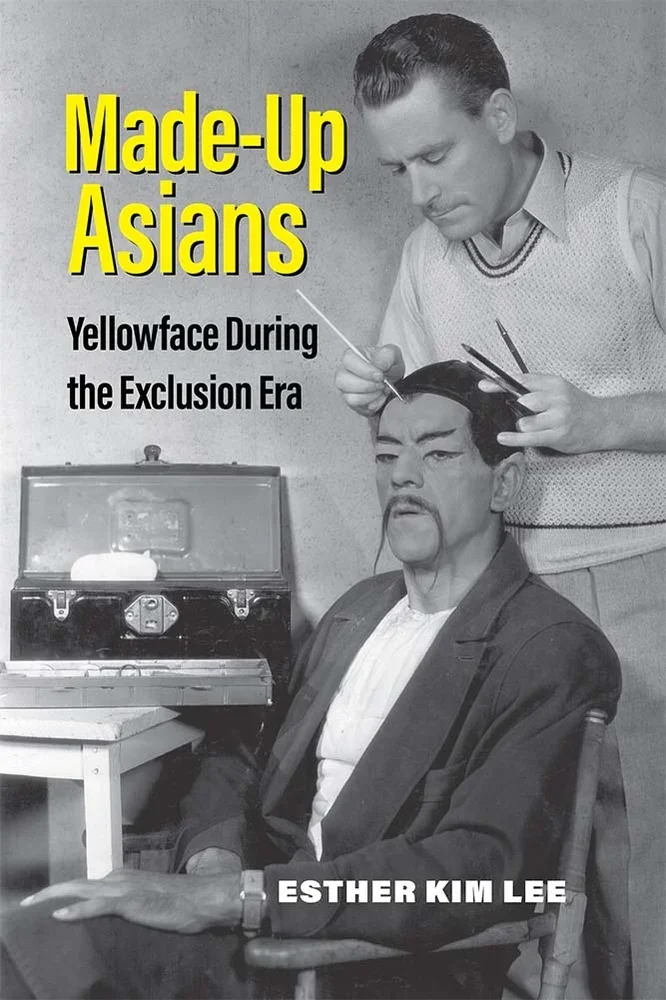

2.2.2 Orientalism, Yellowface, and Western Fantasies

Once an urban attraction across North America, opera theaters in Chinatowns once held Chinese Opera as some of the most substantial entertainment in their diasporic communities. These operas showcased the spectacle of the art, costumes, singing, and feminine displays in falsetto and female impersonations, as true to its opera tradition and similarly to Western opera, casting performers in which they trained and gender was irrelevant, as long as they displayed the vocal and performing style skillset for the role; however these audience experiences and perceptions between Chinese and Western spectators would be very different, in celebration of culture versus a false confirmation of racial fantasy and bias. This would evolve into harmful tropes taken on by stages of the world that would grow in circulation and lead to yellowface and orientalism in opera (Ingraham, So, and Moodley 2016).

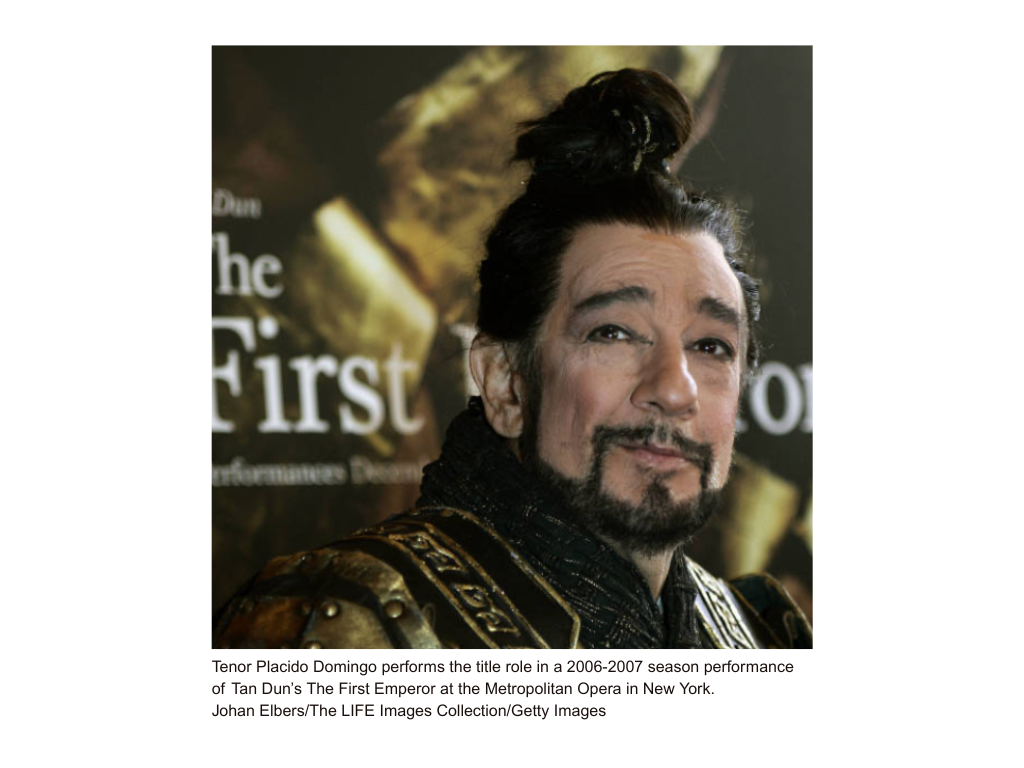

Multitudes of opera written about Asian experiences by White, European men appeared in the late nineteenth and twentieth century on the largest opera stages with works like Reginald De Koven’s The Mandarin [1896], Puccini’s Madama Butterfly [1904], and Turandot [1926], involving caricatures and racial fantasies of Chinese people; however, in a more contemporary work Tan Dun, a Chinese American composer debuted his opera The First Emperor at the Met Opera in its 2006-2007 season as commissioned by the opera house with Chinese film director Zhang Yimou, writer Ha Jin, as well as designer Emi Wada and tenor Plácido Domingo in the title role. Although the Met Opera in a rare moment finally allowed a person of color to tell their own story in their own opera, the public perception as a predominantly White audience took to the opera similarly to that of Chinese Opera as it used to exist in North America with comments of Chinese Opera tropes, “wailing,” and incredulously compared to the Chinese trope in Turandot.[6] Also of important note, even in an opera with Chinese storytelling written by a Chinese composer does Plácido Domingo, a White man, take on the title role of its own opera while donning yellowface—telling of the Met Opera’s diversification at the time.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[6] “The Los Angeles Times on Tan’s dramatically powerful opening scene:

“Chinese and Western opera merge as shaman and yin-yang master sing together. Chorus and orchestra gradually assemble a memorable Chinese folk-like melody. Finally, delightfully out of nowhere, the climax is musically spectacular, a “Turandot” moment, out Puccini-ing Puccini.”

Mary I. Ingraham, Joseph K. So, and Roy Moodley, Opera in a Multicultural World: Coloniality, Culture, Performance, 1st ed., 2015, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315696065.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2.3 Answering the Call to Diversification

From its history it is clear the opera industry in the United States and within the art form is overdue for mass sweeps of progression in diversity in its shows and audiences. Data collected from 1992 on musical theatre and opera arts audiences indicated only 15.3% of the audience for opera in 1992 was nonwhite; Black individuals accounted for 6.6%, Hispanic for 4.4%, Asian for 3.7%, and Native Americans for 0.6% with the proportion of Asians who attend opera being larger than their proportion in the population as a whole (Cherbo and Peters 1992). Opera arts audience demographics data is limited in recent researched literature where calls to DEI practices have been put into place. With this upcoming major shift in diversity in America in the next two decades and the most current available data on opera race audience demographics, the opera industry faces a specific challenge as the industry continues to bring in new audiences into the art form in light of struggles with aging donors and audiences and a history of accessibility barriers in diversity and inclusion.

On top of historical evidence that the opera industry caters to the experiences of Whiteness when it comes to their audiences, BIPOC arts administrators in existing qualitative research have voiced their feelings and experiences on the same phenomena, including the following stated by study respondent on Workforce Diversity in the arts identifying as Black and African American:

“As someone who works in development, I see how audiences and the core donor base are still graying by the day and still are very much White. However, I rarely see strategic efforts made to increase the number of donors or audience members of Color. Is it mentioned in passing? Yes. But the organization I work for has yet to implement anything meaningful to address this issue… If organizations (especially “high art,” historically White arts organizations) don’t make concerted efforts to reach out to diverse populations, then they will continue to be perceived as elitist and exclusive—which are major perceptual barriers to having many People of Color attend ballet, theater, opera, or orchestra performances. (Though it is important to note that many People of Color are interested in seeing artists who look like them and art that is telling a story that they can relate to.) As an administrator of Color, I’ve got a lot to say. We must have diversity in voices. You must have differences of opinion to help create better thinking. That, again, will move the art, absolutely (Stein 2020).”

In another interview by African American identifying interview respondent, Anchorage Opera Executive Director and Artistic Director stated:

“Soon after accepting the position (as the first African American to lead a major performing arts organization in the U.S. circumpolar north), I attended my first Opera America conference. During the first luncheon there were more than 1,200 folks in attendance. I walked in and was immediately struck by the fact that I may have been only African American in the place. My next thought was, “This industry is frighteningly homogenous off the stage. At the same time, I didn’t feel unwelcome. In that moment, I could see “This is the problem. This is it. The lack of diversity behind the scenes.” I had a similar experience in 2000 at my first Association for Performing Arts Presenters (APAP) conference (Cuyler 2021).”

Aside from the opera’s aging audiences, an equally greater threat to the decrease in ticket sales and audience engagement in the opera industry, especially at perceptually elite institutions like the Met Opera, is the diversification of its audience base.

3. Methodology

A mixed method approach of both quantitative and qualitative data was used to investigate how diversity onstage impacts perceptions, barriers, engagement, and experiences of young, diverse arts audiences, singularly looking to the influence the Met Opera holds due to its impact on the industry, their size as a Level A opera institution with the budget size of $15 million and above according to budget range designations by Opera America contributing to its ability for building and creating access in and for the community, as well as its influences on artistic standards that permeate through the rest of the industry, not only physically in person onstage at The Lincoln Center, but also for its reach with their on-demand service, Metropolitan Opera Live in HD that broadcasts nationally in theatres across the country.

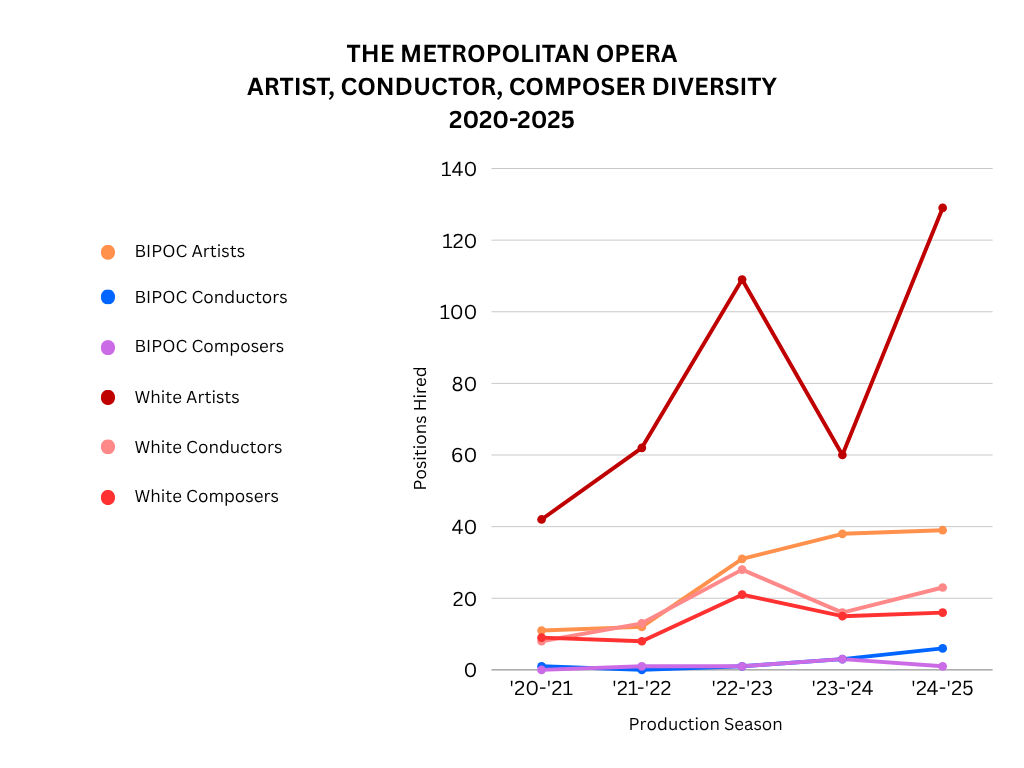

Creating a statistical database, each leading artist casted in the last 5 years at the Met Opera was collected along with their ethnicity and race, and the production and role they were hired in, in addition to conductors and composers to analyze the full scope of diversity and provide more context in productions at the Met Opera in terms of who gets to sing and who gets to tell the story. This data was collected through secondary data using the Met Opera’s casting and production breakdowns online, online programs posted from previous productions, as well as the Met Opera’s online archive which includes the Met Opera’s casting, recording, Metropolitan Opera Live in HD, and production history.

Additionally, the facilitation of an arts audience survey for New York arts audiences 54 and under was conducted online, with 15 questions resulting in 35 participants to gather data on perceptions, barriers, and experiences of opera in order to look further into the relationship between race and diversity at the opera, general perceptions and experiences of the art form and opera spaces, and if instances of race and diversity were a significant factor in those perceptions, barriers, and engagement. This survey was narrowed to New York arts audiences for its likelihood of survey participants having been to the Met Opera before or having the awareness of the Met Opera in order to correlate case study data from the Met Opera’s casting diversity and to maintain a link to experiences to one another as much as possible.

Furthermore, this study involved qualitative research in a series of 13 questions with 3 BIPOC and 3 White active arts audience participants gathered online by random to explore perceptions, barriers, and experiences of arts audiences who have specifically attended the Met Opera to further develop insights on aspects like emotions and feelings that are harder to measure in quantitative research. These questions included feelings of belonging and general thoughts as an opera audience member, thoughts on the opera, and what perceptions of opera were reaffirmed or changed during their attendance.

4. Findings

4.1 The State of Diversification at the Met Opera

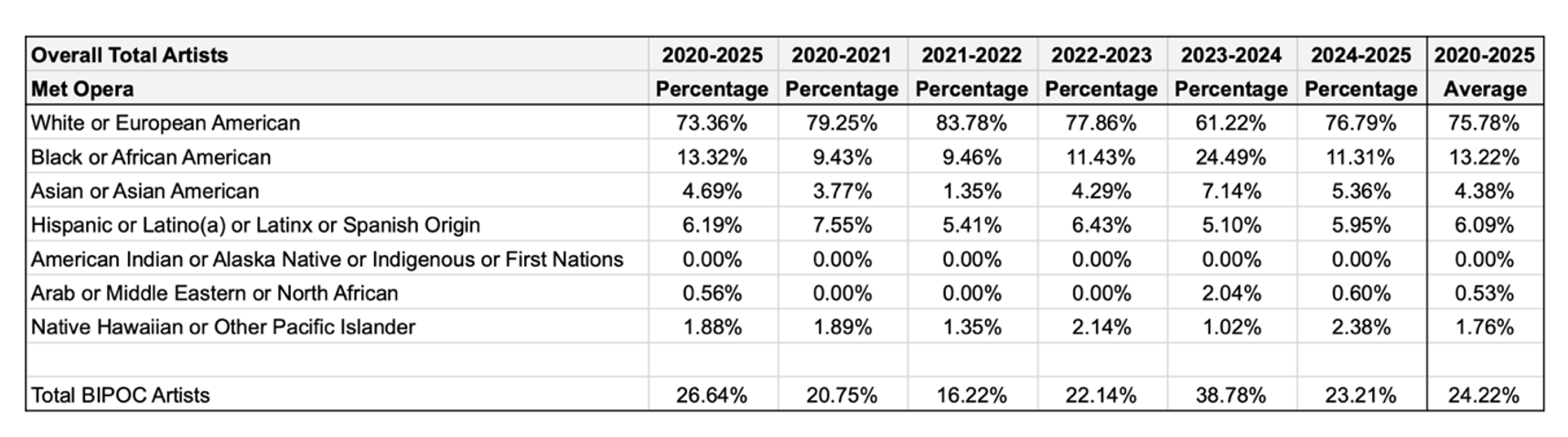

Compiled in the database created for this research of the Met Opera’s last 5 years of opera consists of fiscal year breakdowns from 2020-2025 including 533 BIPOC and White leading role artists, 99 BIPOC and White conductors, and 75 BIPOC and White composers. Of those totals, 142 were BIPOC artists, 11 were BIPOC conductors, and 6 were BIPOC composers. As provided in figure 1, the average percentage of BIPOC artists over 5 years had an increase of 3.47% since the Met Opera’s 2020-2021 season’s 20.75% of roles casted to 24.22% in the next 4 years, while White artists had a decrease of 3.47% in the same timespan from 79.25% of roles casted in 2020-2021 to a 75.78% average in the next 4 years, notably with Black/African American artists at the forefront of average growth at 13.22% followed by Asian/Asian American at 4.38%, and Arab/Middle Eastern/North African at 0.53%. For other groups in the BIPOC community no growth was made for American Indian/Alaska Native/Indigenous/First Nations at 0.00% while Hispanic/Latin(o/a/x)/Spanish Origin and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander had small decreases in average casting.

Figure 1

In its percentages the overall growth for BIPOC artists albeit small shows progress over 5 years at the Met Opera; however, when looking at the number of roles casted per season and the overall percentages of diversity, the disparity appears much more clearly for progress that still needs to be done as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2

With White artists from 2020-2025 at an average casting of 75.78% while BIPOC artists in total sit at an average of 26.64%, audience members are more likely to see White artists when they come to or see representation of the Met Opera, especially considering how decreases shown in figure 2 for BIPOC artists comes at a significant loss due to its already small slot of representation in existence year to year in comparison to any drops in White artists onstage.

In Figure 3, further confirmation is shown in the number of positions hired through 2020-2025 and the large gap in White individuals onstage and in stories at the Met Opera.

Figure 3

These findings point to growth in BIPOC artists onstage for most groups in leading roles in 2020-2025 especially Black and African American artists at the Met Opera and with the exception of the group of American Indian, Alaska Native, Indigenous, and First Nation individuals with zero instances of casting; however, what progress has been made in closing the gap between White and BIPOC groups since 2020-2021, White artists have increased exponentially in the latest 2024-2025 season, creating a large divide in diversity once again with 75% of leading roles cast identifying as White or European American.

4.2 “Otherness” and Intimidation: Opera Patrons, Whiteness, and Wealth

The majority of participants for the conducted survey were White, college educated, age 25-34, and identified as women with incomes $50,000 and above. To further breakdown the race due to its significance of this research, 80% identified as White, 11.4% Black/African American, 2.9% Asian/Asian American, 2.9% Hispanic/Latin(o/a/x)/Spanish Origin, and 2.9% as Multiple. Of this group 25 out of 35 participants acknowledged they had been to an opera before of which 20 said they “rarely (once or twice a year)” attend, 3 they “occasionally (about 3 to 5 events per year)” attend, and 1 “often (more than 5 events per year) attend.”

In the first example of findings from this research, we correlate the level of Whiteness shown at the Met Opera and how it may permeate into perceptions of who “belongs” at the opera as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5 with the most common words used to describe what they imagined as the average opera goer and singer. Of note, 50% of participants responding to “describe what they imagine as the average opera goer” had also said they had never been to an opera before.

When looking to pinpoint barriers to the opera, the top response was cost of tickets with 30 out of 35 respondents as shown in Figure 6, followed by concern about not understanding or lack of knowledge, scheduling conflicts, no one to go with, and intimidated to try in the top five.

Interview participants help provide further context on these barriers with interviewees who had only been to the Met Opera only once had gone with a friend indicated they were unaware low, affordable ticket prices at the opera, especially at the Met Opera, existed and upon the experience had the perception of the ticket cost barrier change. Additionally, those who came with someone noted they would probably not have come to the opera alone for intimidation to be in the Met Opera space alone or intimidation of the art form, feeling as though they would not understand what was going on, however, felt affirmed that they could belong in the space after attendance and seeing that supertitles were provided for translations. Furthermore, of the 6 interview participants, all 3 BIPOC participants mentioned a community aspect was missing from their experience even if they had attended the opera with someone and had desire to see improvement and growth in that realm.

To gain further insight into these issues, interview participants were asked to describe their feelings of belonging. In correlation to survey respondents responding only a “1” or “2” as the lowest feeling of belonging at the opera as shown in Figure 7, of which 50% were BIPOC, responses included negative experiences specifically in relation to their race and microaggressions from White opera patrons. This was further confirmed in interviews where BIPOC participants recalled feelings of “otherness” and discomfort in the space and not wanting to make a mistake, even if they had not experienced direct microaggressions or negative interactions. Notably, discomfort around White patrons that were perceived as wealthy were repeated throughout the interviews; however, discomfort within the space was not mentioned by White interview participants. One interview participant additionally mentioned the surprise of a packed, predominantly White audience existence when they attended a production of Porgy & Bess—a story of Black people with an entire Black cast.

5. Conclusions

These findings confirm diversity onstage and in the opera environment itself impacts the perceptions, barriers, engagement, and experiences for young arts audiences engaging with the opera, especially at large houses like the Met Opera provided the systemic racism deeply embedded within not only the industry in who gets to tell the stories in opera as White artists, but also a catering to Whiteness in audiences that has continued still to this day, permeating into not only the perceptions of people who have and have not attended the opera, but the barriers, engagement, and lived experiences when attending, leaving young arts audience feeling “othered,” especially when they belong to BIPOC groups.

To break down these barriers and soothe perceptions of young arts audiences along with changing the behaviors of current White opera patrons, it would be beneficial to look further into the development and accessibility of young audience community building and opera education at opera institutions. As it currently stands with these barriers, cost is a top barrier and priority in attending the opera of which many existing programs offer; however, the exposure and marketing of these programs and its affordability are lost and non-existent, showing some solutions to young arts audiences’ hesitations in attending the opera are already in place, presenting a feasible solution to build upon at opera institutions—increasing young artist group offerings visibility in messaging and marketing to change the perception that they cannot afford the opera and that community building does exists within the opera industry to not only learn more about opera but build a community of people to go to the opera with.

As for changing the behavior and perceptions of White opera patrons we turn to the need of diversification onstage in the opera industry and within educational programming to bring in BIPOC culture and communities to the opera spaces. White opera patrons have been catered to since the beginnings of opera, causing a lack of exposure to different people, stories, and experiences and it is within opera’s best interest to continue upon the diversification of stories told onstage with BIPOC composers narrating the stories and with BIPOC artists and conductors telling it to position the opera art form and industry as an art that is committed to everyone.

This research is only the beginning of looking into the long, deep history of racial disparity, segregation, racism, and its effects of diversity onstage and its correlations to its diversity in arts audiences in the opera industry today. To further develop insights into this data, institutions at each budget level of opera institutions in America, if not already, should put in place recording for demographic information regarding ticket buyers, honing in on ethnicity and race demographics to compile a better, wholistic picture of how not only the company but the industry is doing in terms of audience diversity development and in which shows they are attending. Furthermore, field research studies conducted by Opera America would benefit industry insights into how the industry in America is performing across the board for diversity in audiences and onstage in its presentations to expand upon and improve this research in the future with a bigger sample size of data collection and evidence.

References:

1. “Metropolitan Opera Archives,” n.d. https://archives.metopera.org/MetOperaSearch/search.jsp?q=%22Sumi%20Jo%22&PERF_ROLE=Gilda&&sort=TI_TINAME.

2. “Metropolitan Opera Archives,” n.d. https://archives.metopera.org/MetOperaSearch/search.jsp.

3. “Soprano Withdraws From Opera, Citing ‘Blackface’ in Netrebko’s ‘Aida’: The American Soprano Angel Blue Said She Would Not Appear at the Arena Di Verona After the Russian Soprano Anna Netrebko and Other Performers Wore Dark Makeup in Its Production of ‘Aida.’” The New York Times. July 15, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/15/arts/music/angel-blue-anna-netrebko-blackface.html.

4. Antonio C. Cuyler, Access, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Cultural Organizations: Insights From the Careers of Executive Opera Managers of Color in the U.S., 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429504174.

5. Brakkton Booker, “Metropolitan Opera to Drop Use of Blackface-Style Makeup in ‘Otello.’” NPR, August 4, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/08/04/429366961/metropolitan-opera-to-drop-use-of-blackface-style-makeup-in-otello#:~:text=Metropolitan%20Opera%20To%20Drop%20Use,:%20The%20Two%2DWay%20:%20NPR&text=Hourly%20News-,Metropolitan%20Opera%20To%20Drop%20Use%20Of%20Blackface%2DStyle%20Makeup%20In,at%20the%20company%20in%201891.

6. Christine Matzke, “Black Opera: History, Power, Engagement.” Studies in Theatre and Performance 42, no. 2 (January 26, 2019): 219–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2019.1573500.

7. Cunningham, Michael, Paramount Pictures, maria manetti shrem, Peter Gelb, jeanette lerman - neubauer, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Kensho Watanabe, et al. The Hours, 2024. https://www.metopera.org/globalassets/season/2023-24/hours-the/programs/052124-the-hours.pdf.

8. Dale Fisher, “Met’s First Opera by a Black Composer Originates in St. Louis.” Nine PBS (blog), March 30, 2022. https://www.ninepbs.org/blogs/press-room/mets-first-opera-by-a-black-composer-originates-in-st-louis/.

9. David Salazar, “Met Opera 2021-22 Season: Here Is All the Information for This Season’s Live in HD Performances.” OperaWire, September 23, 2020. https://operawire.com/met-opera-2021-22-season-here-is-all-the-information-for-this-seasons-live-in-hd-performances/.

10. Francisco Salazar, “Met Opera 2020-21 Season: Here Is All the Information for This Season’s Live in HD Performances.” OperaWire, February 13, 2020. https://operawire.com/met-opera-2020-21-season-here-is-all-the-information-for-this-seasons-live-in-hd-performances/.

11. Giuseppe Adami, Renato Simoni, Carlo Gozzi, GIACOMO PUCCINI, and C. Graham Berwind, III Chorus Master Donald Palumbo. Final Performance This Season, 2024. https://www.metopera.org/globalassets/season/2023-24/turandot/programs/060724-turandot.pdf.

12. Ingraham, Mary I., Joseph K. So, and Roy Moodley. Opera in a Multicultural World: Coloniality, Culture, Performance. 1st ed., 2015. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315696065.

13. Javier C. Hernández, “Audiences Are Returning to the Met Opera, but Not for Everything: The Met Is Approaching Prepandemic Levels of Attendance. But Its Strategy of Staging More Modern Operas to Lure New Audiences Is Having Mixed Success.” The New York Times. June 13, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/13/arts/music/met-opera-attendance.html.

14. Joshua Barone, “The Metropolitan Opera Hires Its First Chief Diversity Officer: Marcia Sells Has Been Brought on to Rethink Equity and Inclusion at the Largest Performing Arts Institution in the United States.” The New York Times. January 25, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/25/arts/music/met-opera-chief-diversity-officer.html.

15. Kunio Hara, “The Death of Tamaki Miura: Performing Madama Butterfly During the Allied Occupation of Japan.” Music and Politics XI, no. 1 (March 1, 2017). https://doi.org/10.3998/mp.9460447.0011.106.

16. Mari Yoshihara, Musicians From a Different Shore: Asians and Asian Americans in Classical Music. Popular Music & Society. Temple University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007760802703351.

17. Metropolitan Opera. “2023-24,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/tickets/group-sales/extraordinary-every-night/2023-24/.

18. Metropolitan Opera. “2024–25 Season,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/.

19. Metropolitan Opera. “A Rare Revival of Gluck’s Orfeo Ed Euridice Opens at the Met on October 20,” October 19, 2015. https://www.metopera.org/about/press-releases/a-rare-revival-of-glucks-orfeo-ed-euridice-opens-at-the-met-on-october-20/#:~:text=Korean%20soprano%20Hei%2DKyung%20Hong,Violetta%20in%20Verdi%27s%20La%20Traviata.

20. Metropolitan Opera. “Aida,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/aida/.

21. Metropolitan Opera. “Aida,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2022-23-season/2022-23-season/aida/.

22. Metropolitan Opera. “Ainadamar,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/ainadamar/.

23. Metropolitan Opera. “Antony and Cleopatra,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/antony-and-cleopatra/.

24. Metropolitan Opera. “Ariadne Auf Naxos,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/ariadne-auf-naxos/.

25. Metropolitan Opera. “Carmen,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/carmen/.

26. Metropolitan Opera. “Cinderella,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/cinderella/.

27. Metropolitan Opera. “Dead Man Walking,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/dead-man-walking/.

28. Metropolitan Opera. “Der Rosenkavalier,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/der-rosenkavalier/.

29. Metropolitan Opera. “Die Frau Ohne Schatten,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/die-frau-ohne-schatten/.

30. Metropolitan Opera. “Die Zauberflöte,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/die-zauberflote/.

31. Metropolitan Opera. “Die Zauberflöte,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/die-zauberflote/.

32. Metropolitan Opera. “Don Carlos,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/don-carlos/.

33. Metropolitan Opera. “Don Giovanni,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/don-giovanni/.

34. Metropolitan Opera. “El Niño,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/el-nino/#:~:text=El%20Ni%C3%B1o%20brings%20together%20three,stage%3B%20and%20pathbreaking%20bass%2Dbaritone.

35. Metropolitan Opera. “Eurydice,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/eurydice/.

36. Metropolitan Opera. “Fedora,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/fedora/.

37. Metropolitan Opera. “Fidelio,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/fidelio/.

38. Metropolitan Opera. “Fire Shut up in My Bones,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/fire-shut-up-in-my-bones/.

39. Metropolitan Opera. “Florencia En El Amazonas,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/florencia-en-el-amazonas/.

40. Metropolitan Opera. “Grounded,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/grounded/.

41. Metropolitan Opera. “Hamlet,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/discover/education/educator-guides-archive/hamlet/.

42. Metropolitan Opera. “Idomeneo,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2022-23-season/2022-23-season/idomeneo/.

43. Metropolitan Opera. “Il Barbiere Di Siviglia,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/il-barbiere-di-siviglia/.

44. Metropolitan Opera. “Il Trovatore,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/il-trovatore/.

45. Metropolitan Opera. “La Bohème,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/la-boheme/.

46. Metropolitan Opera. “La Forza Del Destino,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/la-forza-del-destino/.

47. Metropolitan Opera. “La Rondine,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/la-rondine/.

48. Metropolitan Opera. “Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2022-23-season/2022-23-season/lady-macbeth-of-mtsensk/.

49. Metropolitan Opera. “Le Nozze Di Figaro,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/le-nozze-di-figaro/.

50. Metropolitan Opera. “Les Contes D’Hoffmann,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/les-contes-dhoffmann/.

51. Metropolitan Opera. “Lohengrin,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/lohengrin/.

52. Metropolitan Opera. “Lucia Di Lammermoor,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/lucia-di-lammermoor/.

53. Metropolitan Opera. “Madama Butterfly,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/madama-butterfly/.

54. Metropolitan Opera. “Medea,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/medea/.

55. Metropolitan Opera. “Moby-Dick,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/mobydick/.

56. Metropolitan Opera. “Nabucco,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/nabucco/.

57. Metropolitan Opera. “Orfeo Ed Euridice,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/orfeo-ed-euridice/.

58. Metropolitan Opera. “Part 1 Section 1,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/discover/archives/black-voices-at-the-met/part-1-section-1/#:~:text=The%20Met%27s%20limited%20inclusion%20of,Enlarge%20Image.

59. Metropolitan Opera. “Peter Grimes,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2022-23-season/2022-23-season/peter-grimes/.

60. Metropolitan Opera. “Rigoletto,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/rigoletto/.

61. Metropolitan Opera. “Rigoletto,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/rigoletto/.

62. Metropolitan Opera. “Roméo Et Juliette,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2023-24-season/romeo-et-juliette/.

63. Metropolitan Opera. “Salome,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/salome/.

64. Metropolitan Opera. “Tannhäuser,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/tannhauser/.

65. Metropolitan Opera. “The Magic Flute,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/the-magic-flute/.

66. Metropolitan Opera. “The Magic Flute,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/the-magic-flute/.

67. Metropolitan Opera. “The Metropolitan Opera Announces Its 2022–23 Season, Featuring the World-premiere Staging of the Hours, the Company Premieres of Champion and Medea, and Four More New Productions,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/about/press-releases/the-metropolitan-opera-announces-its-202223-season-featuring-the-world-premiere-staging-of-the-hours-the-company-premieres-of-champion-and-medea-and-four-more-new-productions/.

68. Metropolitan Opera. “The Queen of Spades,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/the-queen-of-spades/.

69. Metropolitan Opera. “Tosca,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/season/2024-25-season/tosca/.

70. Metropolitan Opera. “Tosca,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2022-23-season/2022-23-season/tosca/.

71. Metropolitan Opera. “Turandot,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2021-22-season/turandot/.

72. Metropolitan Opera. “Un Ballo in Maschera,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/un-ballo-in-maschera/.

73. Metropolitan Opera. “X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X,” n.d. https://www.metopera.org/user-information/old-seasons/2023-24-season/x-the-life-and-times-of-malcolm-x/.

74. Naomi André, Black Opera. University of Illinois Press eBooks, 2018. https://doi.org/10.5622/illinois/9780252041921.001.0001.

75. Naomi Andre, Karen M. Bryan, and Eric Saylor. Blackness in Opera. University of Illinois Press eBooks, 2012. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BB17876649.

76. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Performing Arts Workforce, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315642314.

77. Staff, Operawire. “Metropolitan Opera 2023-24 Review: La Bohème.” OperaWire, October 15, 2023. https://operawire.com/metropolitan-opera-2023-24-review-la-boheme/.

78. Stein, Tobie S. Racial and Ethnic Diversity in the Performing Arts Workforce, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315642314.

79. The Metropolitan Opera. “Champion,” 2022. https://www.metopera.org/season/in-cinemas/2022-23-season/champion/.

80. Whyte, William Hollingsworth. The Exploding Metropolis. University of California Press eBooks, 1993. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA21688871.